Unfinished symphonies

15 Dec 2025

News Story

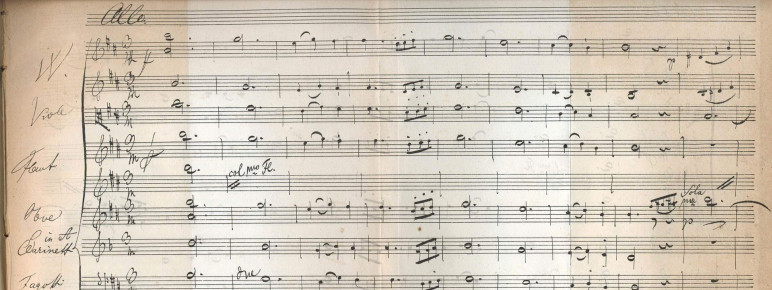

The opening of the 3rd movement (Scherzo) of the Unfinished symphony, as sketched by Schubert (detail).

This article is part of a series for the 2025/26 Season in which we consider different aspects of the symphony – a genre which includes several that aren't actually complete.

There’s such prestige to writing a symphony that the history of classical music is littered with composers who started one but failed to finish it. There are of course plenty of which no-one has heard – by people whose ambition presumably outweighed their ability – but we’ll be charitable and skate right past them to look at some better-known examples. We’ll also leave out works such as Walton’s Symphony No. 1, which was unfinished at the time of its premiere in 1934: the composer struggled with its fourth (and last) movement, meaning the first performance of the complete work didn’t take place until the following year.

One of the most persistent myths about Mozart is that he wrote his manuscripts as though from dictation, each one emerging pristine, devoid of any errors and absolutely perfect. This might suggest that he never started something he didn’t finish, but there numerous examples of works he abandoned partway through, some orchestral pieces among them. Two have been identified as symphonies, both dated May 1782, at a time when he was in the latter stages of writing his opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail – something so demanding on his time that it is not clear why he should have started working on a symphony. Had either project come to fruition, it would have been the first he had written since moving to Vienna, a few months before he started work on No. 35 in D, Haffner (which is completely unrelated to these earlier fragments). As unknown sections of Mozart’s biography go, it’s unlikely to be especially significant, but it's an intriguing little puzzle nonetheless.

Considering how many more symphonies he wrote, it is perhaps surprising that Haydn is believed to have left only one incomplete. Its first movement (the only part which survives) is sometimes used as the overture to his 1770 opera Le pescatrici (The Fisherwomen), the score of which was partially destroyed by fire nine years after its premiere. It’s a typically lively piece of Haydn, so we can take a little comfort from knowing that the music hasn’t gone entirely to waste, even if his operas remain little-known.

Moving on to Beethoven, the only one he left unfinished is what would have been his No. 10, a piece on which he worked sporadically in his final years. Schubert is another matter altogether: he finished seven, with another six surviving in various stages of completion. The one generally identified as No. 8 – the only one with any completed movements, right down to their orchestration – is in a class of its own, to the extent that it is known not as an unfinished symphony but the

Unfinished (which the Orchestra performs in Haydn & Schubert, 15-17 January). Although research has yet to prove conclusively why Schubert put it to one side, perhaps the greater mystery is why he failed to complete so many others.

After Schubert finished the first two movements [of the Unfinished symphony], and wrote out a neat copy, there came a time where he thought this cannot be continued. The form is perfect; there is simply nothing else to say.

The earliest of these, which predates his official No. 1, may well be a case of a young composer biting off more than he could chew (he was only 14 at the time): only 30 bars of it survive. The others are all much more extensive, with the next three all fitting in between Nos. 6 and 8, which leaves something of a stylistic gulf between his early, more derivative symphonies and the later masterpieces. They show Schubert honing his art, clearly wanting to develop his own style but still working out how to do this. What survives of them doesn’t quite go far enough to make their performance viable, as though the composer had realised their shortcomings before he had worked them out down to the finest detail.

The one immediately predating No. 8 is by some distance the most extensive, which may explain why there have been at least four attempts to complete it, hence its identification (in some quarters) as his No. 7. That said, another work of Schubert’s is sometimes substituted for it in complete recordings of his symphonies. This is the 1824 Sonata in C major for piano duet as orchestrated in 1855 – nearly three decades after the composer's death – by the violinist Joseph Joachim, in the (mistaken) belief that it was the reduction of a lost Schubert symphony. We may think we know better now, but this recasting of the so-called Gran Duo still makes for an attractive addition to Schubert’s orchestral works.

As if to show how assiduously the symphony was taken on in the Romantic era, we have to jump all the way to 1910 for the next significant unfinished example. By the time of his death the following May, Mahler had almost finalised the first movement of his Symphony No. 10 and left over 1600 bars of drafted music for the rest of the work – recognised as being of exceptional quality, but not in any condition to allow for its performance. Early attempts to realise the composer’s vision came to nothing, and as the years passed, Schoenberg and Britten were among the luminaries who passed on the opportunity to do so.

There things might have remained, until Mahler’s widow Alma heard the version put together in 1960 by the musicologist Deryck Cooke and gave it her blessing. Not that her approval convinced everyone: a quick look through the available recordings of the Tenth shows a clear dividing line between conductors who have embraced Cooke’s version and those who regard only the first movement as genuine. Eugene Ormandy, Simon Rattle and Yannick Nézet-Séguin are among those who have committed their interpretations of the completed work to disc, counterbalanced by the likes of Leonard Bernstein, Pierre Boulez and Claudio Abbado – so whatever your own view, there’s no arguing you’re in excellent company!

Related Stories

![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!![]()

The medieval carol

24 November 2025

For this year's Christmas article, we look back at some very early festive carols ...