Mozart and the symphony

22 Dec 2025

News Story

Details from three portraits of Mozart: aged 6 (attributed to Lorenzoni), around 24 (attributed to Croce) and 33 (Lange, unfinished).

This article is part of a series for the 2025/26 Season in which we consider different aspects of the symphony – in this case, where does Mozart fit in between Haydn and Beethoven?

Taken in purely numerical terms, Mozart wrote about half as many symphonies as Haydn. The exact number is disputed: there are 106 by the latter, as opposed to somewhere in the 40s or 50s by Mozart, depending on whom you ask. Scale this down to the number that may be considered significant contributions to the genre, however, and the two composers are more closely matched.

Mozart’s are in single figures, while Haydn’s inch their way into double digits – a much greater difference proportionally, but given that the symphony was still a fledgling genre when Haydn composed his first, it’s not particularly controversial to say that it needed a bit of time to mature. By the time Mozart wrote his No. 1 at the tender age of 8, Haydn (then in his early 30s) already had some 20 under his belt, and the symphony came to be one of the genres with which he would most be associated. Mozart was much more innovative when it came to the piano concerto and opera, meaning his symphonies can be at risk of being overlooked – so let us see if we can redress the balance.

Perhaps inevitably for a child prodigy, aspersions were cast on the true authorship of Mozart’s very first symphonies: there were suspicions that his father Leopold had had more than a helping hand in writing them, fuelled by (not unreasonable) doubts that a boy of his age could possibly compose something so demanding. The handful he wrote over the next few years were followed by another larger flurry in the early 1770s, including the first inklings that there would be greater works to come. Despite their numbering, Nos. 25 in G minor and 29 in A are now believed to have been written consecutively, albeit a few months apart. No. 25 has more than a foretaste of the later No. 40 – written in the same key, both being characterised by a nervous restlessness – while No. 29 is sheer joy: expansive and sunny, its drive seems to anticipate Beethoven’s No. 7.

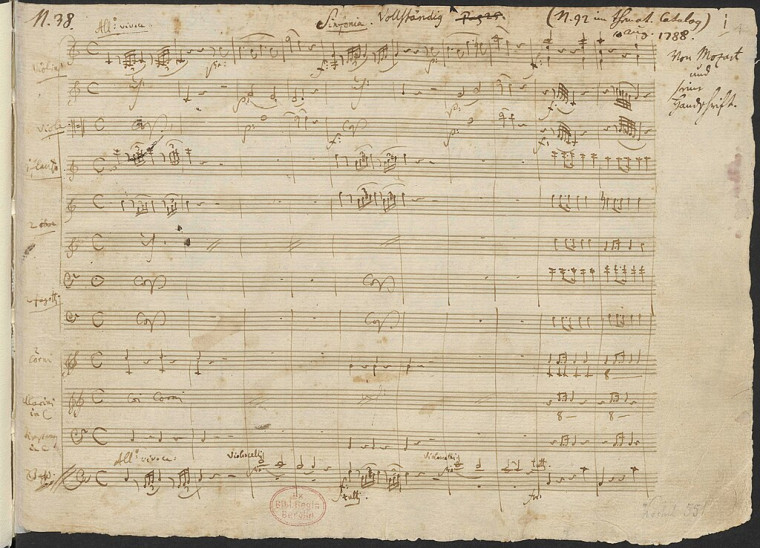

The first page of Mozart's Symphony No.41 (Jupiter), in the original manuscript

This might have marked a sea change in Mozart’s symphonic writing, only the genre’s conventions were not yet set in stone. There would be far fewer lightweight ones – No. 30 clocks in at just over a quarter of an hour, and No. 32 is an underrated little gem that doesn’t even last 10 minutes – but the symphony was slowly growing in scale and importance. Mozart wasn't above indulging his audiences with unabashed crowd-pleasers such as No. 31 (written specifically to suit Parisian tastes) and No. 35 (Haffner), the latter being a late flourishing before his attention shifted to more lucrative genres on his move to Vienna in 1781.

As it turned out, Mozart would write only five more symphonies: Nos. 36 and 38 are named after Linz and Prague respectively – the cities where they received their premieres – but the origins of Nos. 39-41 are murkier. (For anyone keeping track, No. 37 is in fact Michael Haydn's No. 25, to which Mozart appended a slow introduction.) Unusually for Mozart, no evidence has come to light proving that these last three symphonies they were ever performed in his lifetime. According to one theory, he may have written them purely to satisfy a creative urge - though No. 40 in G minor exists in two different versions (the original one having had no clarinet parts), which would suggest a change in the available orchestra.

It’s also been suggested that Mozart intended them as a triptych, the warmth of No. 39 being followed by the fraught emotions of No. 40, washed away by the No. 41's jubilation. It’s a view supported by the speed at which he wrote them, between June and August 1788, and if we should look on them as a set, it's further evidence of how much the symphony had expanded during Mozart’s lifetime. You can hear all three in – appropriately enough – Mozart's Last Three Symphonies (29-31 January).

The symphony's growing stature as the 18th century gave way to the 19th means that the symphonic trilogy never really took off as a genre, despite Haydn having got the ball rolling with his Nos. 6-8 (Morning, Noon and Evening) all the way back in 1761. Writing a single one has been deemed sufficient of an undertaking ever since, expected to be sufficiently imposing for it to be appreciated on its own merits, unsupported by others. Whether or not Mozart intended his final three to make up a larger whole, they stand as the pinnacle of his contribution to the history of the symphony. His specific role may be harder to pin down, but if we extend the family metaphor begun with Haydn as the father of the genre, perhaps we should call him its cousin?

Related Stories

![]()

Making a splash: water music beyond Handel

5 January 2026

We take a look at musical depictions of water, from trickling burns to the wide expanse of the ocean, to see what lurks below the surface.![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!