The medieval carol

24 Nov 2025

News Story

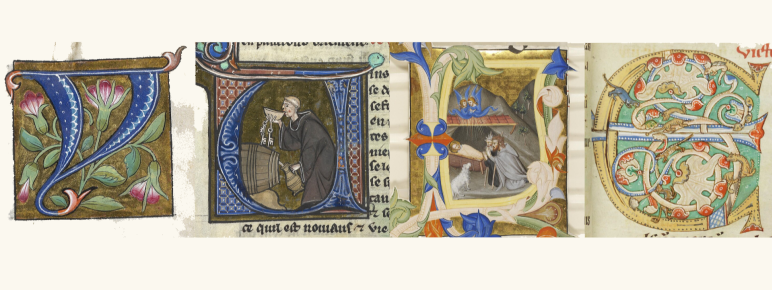

A festive (if pagan) word spelled out in illuminated letters, from a variety of medieval manuscripts

This time last year, we looked at the origins of a wide variety of Christmas carols. The texts in Britten’s A Ceremony of Carols, the centrepiece of this year’s Christmas concerts by the SCO Chorus (21-22 December), come from an earlier period than any of those we covered then, a perfect excuse to examine the early history of the genre through the carols the composer set in this work.

A single book, the 1923 anthology The English Galaxy of Shorter Poems, served as Britten’s source, though its contents extend far beyond the 15th and 16th century festive poetry he selected. Widely read, Britten had already shown his affinity with literature of this era, having previously set other carols from what we would now term the Early Modern Period (and Christina Rosetti’s In the bleak midwinter) in A boy was born.

Long predating any standardisation of English, one immediately obvious feature of these texts is the language: a good deal of it is in old English, or more accurately a mixture of Middle and Early Modern English. In performance, the words are generally sung with modern pronunciation (it’s easier for the audience as well as the choir), at least until the text suddenly veers into Latin. This generally indicates a carol of a more religious bent, free of references to Yule and other pagan festivals – not that the original tunes bother to differentiate between these two traditions. If Britten doesn’t quite follow in this vein, his deliberate juxtaposition of sacred and secular texts also harks back to Medieval habits.

The decidedly secular ‘Wolcum Yole!’ (‘Welcome Yule!’) is followed by the quiet reverence of ‘There is no rose of such vertu’ – a poem in which English moves nonchalantly into Latin (and back again) with the same ease as a parallel is drawn between the purity of a rose and the Virgin Mary. This same seeming disparity can also be found throughout ‘In dulci jubilo’, though in that case the occasional Latin phrases cannot temper the joyous dance rhythms in the music.

‘There is no rose of such vertu’ is notable as one of the rare texts from A Ceremony of Carols to be well-known in other settings. In common with many other Medieval carols, there is an enormous gap between its original version (for two voices, written around c. 1420) and later ones, which date from after the First World War. The catalyst for this revival of interest in older texts was most likely the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols becoming a firm fixture in the Anglican church calendar from 1918. Leaving aside congregational hymns, the choir’s contributions to this service often open with ‘Adam lay ybounden’, another Medieval carol. Its original music has long since been lost, leaving us only with more recent settings, of which the most popular (by some margin) is by Boris Ord.

Britten's response forms the penultimate movement of A Ceremony of Carols, an apt choice given that its closing line of ‘Deo gracias’ – ‘Let us give thanks to God’ – suggests the end of a church service. This is reflected in the composer’s framing device, a Gregorian chant-like setting of the words ‘Hodie Christus natus est’ (‘Christ is born today’) with which the work both opens and closes.

In ‘That yongë child’ and ‘Balulalow’, the focus shifts to the sleeping Jesus. The words of the former remain little-known (possibly not helped by their relative brevity), but ‘Balulalow’ (a lullaby) has its roots in a 16th-century translation into Scots of ‘Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her’, a Lutheran hymn used on several occasions by Bach – including in music for solo organ, ensuring its use as a voluntary in carol services to this day. The next carol, ‘As dewe in Aprille’ is also more familiar under a different title: as ‘I sing of a maiden’ (its first line), it has been set by everyone from Quilter (more familiar as a composer of art songs) to John Adams, introducing his nativity-themed oratorio El Niño.

Separated by an interlude for solo harp, the next two poems are both by the Jesuit priest Robert Southwell. ‘This little Babe’ describes a dramatic battle between good and evil, as represented by the infant Christ and Satan respectively, a subject sufficiently far removed from the popular idea of Christmas that it was never likely to be a favourite with congregations. (The Massacre of the Innocents, as retold in the Coventry Carol, at least fits within the narrative of the Nine Lessons and Carols.) The humble circumstances of Christ’s birth, as alluded to the text of ‘In Freezing Winter Night’, make for a rather easier listen, though like ‘This little Babe’, this poem’s status as a carol – at least in our modern understanding of the term – may be questionable.

The same might be said of ‘Spring carol’, which looks forward to signs of rebirth in the natural world. Like MacMillan’s Veni, Veni Emmanuel (which you may have heard at the beginning of the current SCO Season, played by Colin Currie), this places the festive season within a wider context. The Medieval carol was not limited to Christmas: there are examples associated with other times of the year, to say nothing of those with pagan rather than Christian origins. It is testament to Britten’s genius that his choice of texts should reflect the wide scope of the carol at the time they were written.

Related Stories

![]()

Making a splash: water music beyond Handel

5 January 2026

We take a look at musical depictions of water, from trickling burns to the wide expanse of the ocean, to see what lurks below the surface.![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?