The percussion concerto

1 Sep 2025

News Story

SCO Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin (photo credit: Ryan Buchanan)

This article is part of a series focusing on the concerto as written for specific instruments in the orchestra. With contributions from SCO players, we hope these give you some new insight into works you know and an idea of others they would recommend seeking out.

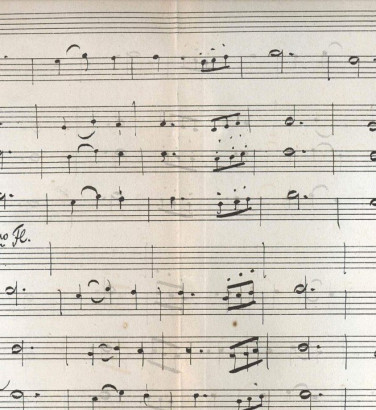

You might reasonably think that the percussion concerto is a recent phenomenon, something no composer would have considered until the section had grown sufficiently to make writing one a worthwhile project. That, however, would be reckoning without 18th-century aristocrats’ taste for the unusual, which in 1780 resulted in Johann Christian Fischer writing a concerto in which one percussionist has eight timpani at his command – which, sad to relate, is where this work’s interest stops. To modern ears, Philidor’s earlier Bruit de timbales (sometimes used as an introduction to Charpentier’s Te Deum) is perhaps more memorable, if only because there’s something faintly ridiculous about a march for nothing but a pair of drums.

All this to say that, while there is precedent for the modern percussion concerto, it’s difficult to see past the curiosity value of earlier examples. There would be an enormous gap before what we would now recognise as a percussion concerto would be written, but composers put that time to good use, exploring the potential of a vast array of percussion instruments in an orchestral context, long before anyone thought of placing them centre stage. It is in this earlier repertoire that Louise Lewis Goodwin, the SCO’s Principal Timpanist, is truly at home, enjoying “the groundwork that is laid for [later] composers to springboard off”.

A quick word about Louise's title, which is officially Principal Timpani with Percussion. By her own estimation, she plays the timpani around 80% of the time, and will step in to play other percussion instruments as necessary. When the Orchestra performs repertoire requiring another player, the latter will take primary responsibility for the wider percussion while she remains at the timpani.

Going back to the early days of the timpani in the orchestra, there’s something rather special about those works they introduce alone: where would the exuberance of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, the mysterious opening to Haydn’s Symphony No. 103 (aptly named Drum Roll) or the quiet lyricism of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto be without their opening gestures from the timpani? With only a pair of them to hand, it takes a bit of effort – and imagination – to write well for them, and all three of these composers excelled at it.

Beethoven pushed the boat out a little when adapting his Violin Concerto for piano and orchestra, going as far as to have the timpani join the soloist in the first movement’s uproarious cadenza. This unusual duet was recreated in the SCO’s performances of the original violin version on their European tour earlier this year, with Louise clearly enjoying sharing the spotlight with violinist Vilde Frang. There’s no reason to suppose Beethoven knew Mozart’s early Serenata notturna, a little gem in which two small string ensembles (one of them bolstered by a pair of timpani) are pitted against each other, but the effect is much the same. SCO Principal Guest Conductor Andrew Manze’s 2003 recording of this work throws in an impromptu timpani cadenza in the last movement, adding to the fun of the piece.

Staying with the timpani (the only percussion with a fixed place in the orchestra until well into the 19th century), one of its earliest truly imaginative uses came in Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, in which a distant rumble of thunder is heard towards the end of the third movement. Quiet drum rolls on four timpani may not sound particularly exciting, but the atmosphere – already unusually bleak in what is supposed to be a pastoral setting – immediately turns ominous, even though we never hear the storm break. The tension is ramped up in the next movement, a march to the scaffold in which the timpani are joined by cymbals, a snare drum and bass drum. Berlioz sets himself out as a precise orchestrator with all sorts of detailed instructions to the percussionists here, not least the direction that the timpanists should play “the first quaver of each beat […] with both drumsticks, the other five with the right-hand stick only”. (The result should be terrifying, but often comes off as utterly thrilling instead.)

As the orchestra expanded over the next century or so, the percussion family grew with it, to the extent that larger scores often required two timpanists among its players. With regards to the other instruments in the section, music that included some of the outliers became especially memorable: Tchaikovsky turned to the newly-created celeste to depict the Sugar Plum Fairy his ballet The Nutcracker (which the SCO performs in full, 3-5 December), while Mahler’s Symphony No. 6 requires no fewer than 6 percussionists in addition to a pair of timpanists, on instruments including a hammer. The composer – following Berlioz's example – stipulates that its sound should be akin to the fall of an axe, “short, powerful, but dull in resonance, not metallic”; this is often rendered by striking a hefty block of wood with an equally enormous wooden mallet. Even Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring comes off as relatively modest by comparison, with a mere three percussionists (again over and above the timpanists).

The timpani might have been left behind amid all this exotica were it not for a key innovation in their design in the 1880s. They had up to this point been possibly slightly hampered by being limited to playing the single note to which they were tuned, but the development of a quick method of retuning by means of a foot pedal made this a thing of the past. This went far beyond altering their pitch in passages when they weren’t being played: Bartók, in his 1936 Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste, makes a feature of changing the note during a quiet drumroll, to eerie effect.

20th-century composers had also started considering percussion in other contexts, including as part of small ensembles. In 1918, Stravinsky made room for a percussionist in The Soldier’s Tale ensemble of seven musicians – a work Louise deems particularly worthy of mention – but a percussion part in the finale of Pavel Haas’ 1925 String Quartet No. 2 proved so controversial that the composer later marked it optional. (Fast forward to the 1950s, when Britten included percussion in the chamber ensembles of his opera The turn of the screw and the War Requiem, and no-one batted an eyelid.)

Varèse wrote the first piece of music for percussion ensemble, Ionisation, in 1929-31, though some argue Antheil beat him to it with his 1924 Ballet mécanique (which includes several pianolas, whose status as percussion instruments is debatable). Then there’s Ligeti’s opera Le grand macabre, which opens with a modestly-scored prelude for (of all things) a dozen car-horns, generally played by three people, each holding four old-fashioned klaxons: one in each hand and another under each foot. With a trayful of crockery among the other percussion instruments, it comes tantalisingly close to being written for everything including the kitchen sink.

Given the range of percussion in use (however occasionally) at this point, playing these instruments unsurprisingly started to become an attractive proposition for young musicians. This was certainly true of Louise, for whom “the sheer variety of instruments that are encompassed beneath that umbrella term” was an immediate draw. She relished the opportunity to try out the range of disciplines on offer, covering “solo marimba, jazz vibes, Latin percussion, orchestral percussion, timpani, multi-percussion solos and about a million other things.” She does point out, however, that “the further you upskill, the harder it is to keep all those plates spinning”, meaning that the young player does eventually have to specialise in “a few of these areas”.

Louise is therefore less familiar with the concerto repertoire for solo percussion – she admits that “Beethoven really is much more my jam” – so her recommendations come from her perspective as an orchestral percussionist. As the SCO’s sole percussionist, she particularly enjoys those occasions that call for the assistance of a second player: among her favourite works in this category are Milhaud’s jazz-infused La création du monde and Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 14 (scored for soprano and bass soloists, with an orchestra of strings and percussion only).

The timpani concerto made a minor comeback towards the tail-end last century, but it had arguably been eclipsed by those for the marimba. Although the instrument has its origins in 16th-century Latin America, it wasn’t until 1940 that it received its first solo concerto, from the pen of one Paul Creston. It was then paired with the equally modern-sounding vibraphone for a double concerto by Milhaud in 1947, and if the marimba concerto hasn’t quite taken off as a major genre, it clearly has its aficionados: the Danish composer Anders Koppel, for example, has contributed four to the repertoire, mostly for the Austrian percussionist Martin Grubinger.

The concerto for multiple percussion, on the other hand, has had much longer staying power, possibly in part due to the visual element that arises from seeing a single player performing on several (often less familiar) instruments. Scottish musicians have proved to be true pioneers in its popularity: Evelyn Glennie is credited as the first person to have made a lasting career playing percussion as a soloist, and many cornerstones of the percussionist’s concerto repertoire owe their existence to her. First and foremost among these is Veni, Veni Emmanuel, Sir James MacMillan’s 1992 exploration of the Advent hymn of the same name (and an SCO commission). Her fellow Scot Colin Currie, in his mid-teens at the time it was written, quickly added it to his own repertoire, and joined the SCO to perform it on the second leg of our 2025 European Tour and in the opening concerts of our 2025/26 Season.

The admittance of percussionists to BBC Young Musician in 1994 tied in with the percussion concerto really taking off that decade. The winner of the percussion category in that inaugural year was Colin Currie himself, and a mere four years later, Adrian Spillett went on to win the competition outright. Like Louise, his primary work is now as part of an orchestra, but Evelyn Glennie and Colin Currie between them have premiered a majority of significant additions to their concerto repertoire since, with Currie gradually taking on the mantle from Glennie.

Among them, it’s worth highlighting the (superficially) similar approach taken by Thea Musgrave in Wood, Metal and Skin (each movement being named after the type of percussion instrument featured) and John Corigliano in Conjurer, which highlights the same instruments in the same order. Ned Rorem limited Glennie’s arsenal of instruments to tuned percussion in his Mallet Concerto, while Currie discovered new soundscapes in concertos by the Finnish composers Einojuhani Rautavaara and Kalevi Aho. Breaking up this duopoly, Avner Dorman wrote his crowd-pleasing Frozen in Time for the afore-mentioned Martin Grubinger, and Jennifer Higdon added to the theatricality of the genre with her Duo Duel, a concerto for two percussionists. In the midst of all this, Sir James MacMillan – the composer who might be said to have started it all – became that rare thing in 2014, a composer with a Percussion Concerto No. 2 to his credit, written for and dedicated to Currie.

Today, the popularity of the percussion concerto shows no sign of abating. If anything, it has made the prospect of being a percussionist even more attractive to young musicians: there are almost as many possible disciplines to consider (and avenues for performance) as there are instruments to play.

Related Stories

![]()

Making a splash: water music beyond Handel

5 January 2026

We take a look at musical depictions of water, from trickling burns to the wide expanse of the ocean, to see what lurks below the surface.![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?