Beyond the Sugar Plum Fairy: a short introduction to the celeste

3 Nov 2025

News Story

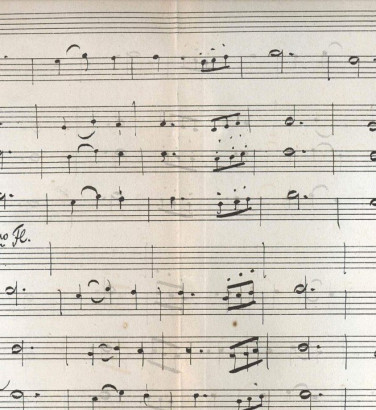

A look inside the celeste (a Schiedmayer model)

The use of the celeste to represent the Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker – which the SCO performs in full, 3-5 December – may not have been the first time it was heard in the orchestra, but it remains by some distance the most iconic. Tchaikovsky had been determined to give it a starring role before Rimsky-Korsakov (a master orchestrator) could discover its captivating sound, but had already included it (less prominently) in his symphonic poem The Voyevoda the previous year. Even then, its first known use had been back in 1888, as part of incidental music for Shakespeare’s The Tempest written by the French composer Ernest Chausson in 1888 – appropriately enough, it is first heard accompanying the spirit Ariel.

An instrument that looks like a small upright piano, playing its keys causes a set of hammers to hit metal plates positioned over wooden resonators, creating a soft, bell-like sound. Chausson and Tchaikovsky alike recognised its ability to convey an ethereal soundscape, something captured so well in The Nutcracker that other composers have had to explore its potential elsewhere, for fear of comparison. Holst’s The Planets, for example, ends with the mysterious sound of an off-stage female chorus, but only after some delicate figurations on the celeste have set the scene. (It’s one example among many of the debt John Williams’ film scores owe to Holst: in the Harry Potter films, the celeste introduces Hedwig’s Theme – named for the title character's owl – before taking flight in some gossamer-light scales that swoop and dive with dizzying grace.)

Mahler (not a man to shy away from writing for huge orchestras) uses the celeste sparingly, maximising its effect – albeit while recommending it is doubled, if not tripled, in his Symphony No. 6. It gets a little solo in Gershwin’s An American in Paris, leaving the distinct impression of a composer enjoying exploring all the contents of his musical toybox, while at the other end of the spectrum, a key component of the chilly ending to the first movement of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 is a repeated upward scale on the instrument.

Bartók singled it out in the title of his Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste, pointing to its central role in the music: first heard towards the end of the first movement, its shimmering accompaniment to the strings’ sinuous lines is thoroughly unsettling. Britten would capitalise on this further still in his opera The turn of the screw, in which the first mention of Peter Quint (the deceased valet of the house) is heralded by the celeste. Its figurations are at once mysterious and alluring, with a sinister edge to match the character.

Perhaps the most surprising development in the relatively short history of the celeste (2026 marks only the 140th anniversary of its invention) has been its adoption outside the classical sphere. It’s prominent in Buddy Holly’s 1957 single Everyday, and the rollcall of artists who picked up on its sound over the next few decades makes for very impressive reading: take your pick from Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, the Beatles, Rod Stewart, Nick Drake, Pink Floyd and Björk and you’re still barely scratching the surface – even a-ha got in on the act in 2017. Among all these, however, it’s fair to say the true standout is the inimitable Kate Bush, who employed its sound to eerie effect in her debut single, the equally haunting Wuthering Heights.

Related Stories

![]()

Making a splash: water music beyond Handel

5 January 2026

We take a look at musical depictions of water, from trickling burns to the wide expanse of the ocean, to see what lurks below the surface.![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?