Symphonies and their nicknames

8 Sep 2025

News Story

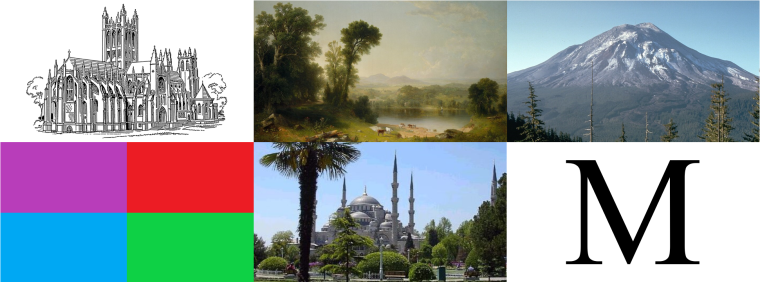

Can you name the symphonies whose nicknames are represented here? Answers at the bottom of the page.

Following our concerto series in 2024/25, this Season we turn our attention to the symphony. To kick things off, here's a look at the names by which some of them are better known.

Forming the backbone of many an orchestral concert, the symphony is perhaps the most-written genre of classical music. Very few of the major composers have avoided it altogether, so composing one can be something of a rite of passage. Long before anyone had any idea how popular it would become (or that numbering them could be a good idea), ascribing a suitable nickname to a favourite symphony became an attractive way of marking it out from the crowd.

This was generally the audience’s doing rather than the composer’s, though the balance started to shift during the 19th century. The earliest symphonies to have gained names may well have been Haydn’s Nos. 6, 7 and 8, known as Le matin, Le midi and Le soir respectively (Morning, Noon and Evening). These are indicative of perhaps the largest category of nickname: the broadly pictorial, arising either from the character of the symphony as a whole or a specific section conjuring up a particular mental image.

There are many instances of this in Haydn’s alone, from the readily understandable (No. 101, Clock, features a tick-tock accompaniment in its second movement) to the obscure (No. 63, La Roxelane, being based on incidental music he had written for a play of this name); click here for a comprehensive guide. Others are a little vaguer: one of the many theories behind Mozart’s No. 41 being known as the Jupiter is that the music brought to the mind of one early listener the Greek god’s thunderbolts – not that this has stopped record labels from issuing recordings with the planet Jupiter on the cover.

When a symphony gains a name from its composer, this can be expected to give an indication of its overall mood or theme, such as Tchaikovsky’s No. 6, Pathétique (a name actually suggested by his brother Modest) and Bliss’ A Colour Symphony (in which he depicts their meanings in heraldry). Among lesser-known works, Dittersdorf’s include a set known collectively as the Ovid Symphonies, each given an individual title explaining which part of the Roman poet’s Metamorphoses served as its inspiration. In Beethoven’s No. 3, we have an instance of a change of name between composition and first performance: originally to be called Napoleon, the composer famously changed this to the more generic Eroica, meaning heroic, when Bonaparte declared himself Emperor and (in Beethoven's view) betrayed the principles of the French revolution.

Speaking of Beethoven, if you were wondering how this could possibly tie into his (nameless) Symphony No. 5 – which the Orchestra plays in From Darkness to Light (2-4 August), opening the 2025/26 Season – there have been various attempts (including a 1963 recording by Bruno Walter, shown below) to market it with the nickname Fate. A clear reference to the tale told (many years after the event) that Beethoven had described its opening motif as Fate knocking at the door, the unreliability of its source – the composer’s secretary Anton Schindler – does nothing to help a nickname that is a bit trite, especially compared to the magnificence of the music. Saint-Saëns’ Symphony No. 3, Organ, is also in this vein, a masterpiece that has transcended the rather dull title its composer gave it: Symphony avec orgue (Symphony with organ) is so lacking in poetry that it sounds more like a placeholder name.

There is, however, a long history of symphonies whose rather literal names suit them well. Prokofiev’s No 1, Classical, lives up to its name in terms of its proportions, the size of the orchestra and being a stylistic tribute to Haydn, while Berlioz’ Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale is exactly what it says on the tin: grand, funereal and triumphal all in one. The one thing this title fails to mention is that it is scored for military band, with optional choir and strings.

An even greater sense of scale is evident from the nicknames of Mahler’s No. 8 and Havergal Brian’s No. 1. The former is known as the Symphony of a Thousand, a comment on the enormous number of performers it requires: at least 4 of each woodwind instrument, twice the number of brass, 8 percussionists, 4 different keyboard instruments and a string section to match … not to mention 8 vocal soloists, a children’s choir and 2 adult choirs. The idea of a thousand performers being involved is actually an exaggeration, but as much Mahler disliked the name, it’s an understandable bit of hyperbole.

Brian’s Symphony No. 1 is scored for even larger forces (such as four off-stage brass bands, each made up of 9 players) and typically lasts around ten minutes shy of two hours. As such, you might think its nickname, Gothic, is very apt in describing its size, but the title actually refers to the artistic movement of the late medieval period. There is something of this style of architecture in the monumental final movement, in which the addition of voices (including a children’s choir and four adult ones) gives a distinct impression of a vast cathedral of sound.

Unlike Mahler’s Symphony No. 8, however, which is performed occasionally, Brian’s Gothic is so enormous (not least in the demands on its performers) that its outings are very few and far between. For starters, it was completed in 1927 but remained unperformed until 1961, and according to the Havergal Brian Society website, complete performances of the Gothic had still not reached double figures by the time their listings stop in 2017.

Staying with English symphonic composers, Vaughan Williams is an unusual case, in that he gave titles to four – A Sea Symphony, A London Symphony, A Pastoral Symphony and Sinfonia antartica, which would have been Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 7 – and numbered the other five around them. The London falls within another prominent category of nicknames, but actually shows the perils of attaching too much significance to placenames used in this context. Vaughan Williams’ music recreates various sounds heard across the British capital, such as the chiming of Big Ben and the (now less familiar) song of lavender sellers, but the composer later suggested Symphony by a Londoner would perhaps have been a more correct name.

It does, however, conjure up the city’s soundscape more than Haydn’s No. 104 of the same name, whose association with London is rather arbitrary. Yes, it was written for performance there, but so were the previous eleven, and the complete set is known (slightly confusingly) as the London Symphonies. Other symphonies named after specific places are almost too numerous to mention: they extend far beyond Linz and St Petersburg (after which Mozart’s No. 36 and Shostakovich’s No. 7 are named, the latter under its then name of Leningrad) to cover every corner of the globe. To name but three examples, Hovhaness’ No. 50 (Mount St. Helens) depicts this volcano’s devastating eruption in 1980, Turina’s Sinfonia sevillana is named after his native Seville and Cowell wrote his No. 13 (Madras) after returning from studying Indian classical music in the city now known as Chennai.

We should also mention symphonies inspired by wider geographical areas, their composers drawing inspiration from less specific sources. These include Mendelssohn’s Nos. 3 (Scottish) and 4 (Italian), while at a greater distance from standard SCO repertoire, we find the likes of Strauss’ Alpine and Beach’s Gaelic symphonies, the latter based on music drawn from the length and breadth of the Gaelic-speaking world. D’Indy’s Symphonie sur un chant montagnard français (Symphony on a French Mountain Air), in the meantime, may be built on a folk song he had heard in the Cévennes mountains, but there is no attempt to make the music evocative of the region.

Overall, however, a symphony’s nickname (especially one given by the composer) can be expected to give a foretaste of what is to come, especially when they tend towards the poetic. Górecki’s Symphony No. 3 is very much the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs of its title, while the mystery of MacMillan’s No. 5 is compounded by his French title Le grand Inconnu (The Great Unknown, in reference to the Holy Spirit). Given the vastness of the repertoire, there are countless examples of little-known symphonies with wonderfully evocative titles: Kolodub’s No. 3, Symphony in the style of the Ukrainian Baroque, and Fazil Say’s No. 1, Istanbul, for example, cast light on parts of the world often overlooked by the classical sphere.

Nicknames for works in this seminal genre may no longer be the preserve of audiences, but thanks to composers like Alberto Williams – whose oeuvre includes nine symphonies, The Sacred Forest and The Death of the Comet among them (Nos. 3 and 6 respectively) – their names still have the power to spark the imagination of music lovers everywhere.

Top row, from left to right: Brian Symphony No. 1 (an example of Gothic architecture), Beethoven Symphony No. 6 or Vaughan Williams A Pastoral Symphony (Durand's Pastoral Landscape), Hovhaness Symphony No. 50 (Mount St Helens, pictured before its eruption in 1980)

Bottom row, from left to right: Bliss' A Colour Symphony, Fazil Say Symphony No. 1 (the Grand Mosque in Istanbul), Mahler's Symphony No. 8 (a thousand, in Roman numerals)

Related Stories

![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!