A history of the orchestral concert

17 Nov 2025

News Story

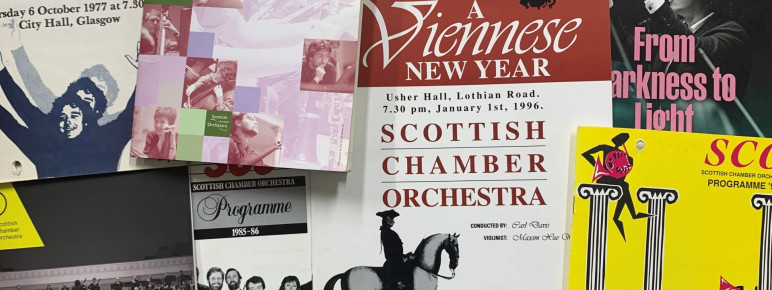

SCO programmes over the decades

Look through any orchestra’s season brochure and chances are that you’ll find more than one performance consisting of an overture (or other short work for orchestra), a concerto and a symphony. Two of our own concerts this Season have followed this exact format (with more to come), so there’s a reason it has become something of a standard: the overture works as a sort of appetiser, allowing the audience to settle in – and any latecomers to be admitted – before the weightier material. A guest soloist then steps into the spotlight for a concerto (providing a contrast to purely orchestral works) and after the interval, the focus reverts to the orchestra for a momentous symphony.

It wasn’t ever thus, however, and we should probably beware of thinking this was ever the norm. The design of a concert programme is ever-evolving as new ideas are tried out and tweaked in endless variety, and there is no end of performances which don’t follow this model. There could be a choral work somewhere along the line, for instance, or the organisers may decide to forego the overture altogether and launch straight into more substantial fare. Other programmes may be designed along more free-wheeling lines, with a carefully-curated sequence of music that flows naturally from one piece to the next, and a couple of unexpected juxtapositions for good measure. Some larger works may even be performed on their own, the argument being that they are so all-encompassing that they don’t anything else to prop them up: some Mahler or Shostakovich symphonies certainly qualify, and (moving away from orchestral repertoire) the same could be said of works like Bach’s Goldberg Variations or Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor.

For the sake of simplicity, however, let us take the overture-concerto-symphony format as a (very malleable) standard. How did we arrive here?

Public orchestral concerts are actually a comparatively recent phenomenon: many of the earliest orchestras were in the employ of aristocratic families, for their private entertainment. Public performances tended to be limited to sacred music (albeit within the context of the church liturgy), social occasions such as dances (formal and informal alike) and the opera house. There were exceptions, one of the most famous being the concerts led by Telemann (and later JS Bach) at the Café Zimmermann in Leipzig from 1720-41, in which orchestral music was among the pot-pourri of works played to the customers of this fashionable coffee house.

What we now recognise as a symphony came together in the latter half of the 18th century, but it did not yet occupy a central position in orchestral performances. It was in fact perfectly normal for its movements to be divided up over the course of a concert, with a good deal of other music being added between them – generally all involving the orchestra, but with popular soloists taking guest spots. It is this kind of concert which serves as the inspiration for our Mozart Matinee concerts (17-19 December): the composer’s 'Posthorn' Serenade will be performed in full, its seven movements being interspersed with music from a variety of his operas.

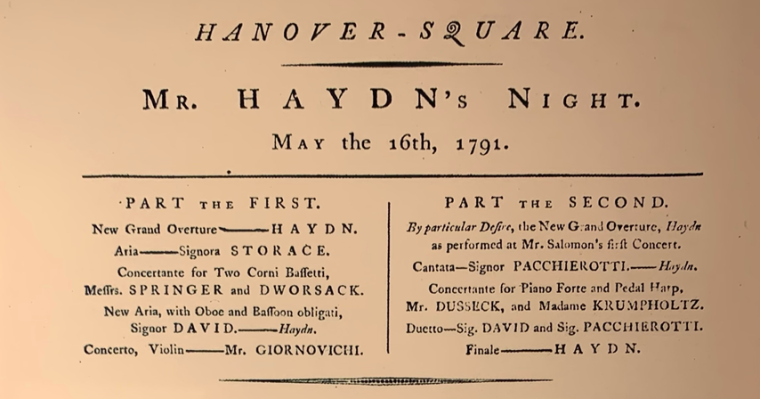

The aristocracy’s grip on exclusivity was already starting to slip. They had once had more-or-less exclusive rights to a work’s premiere before there was any possibility of the wider public getting to hear it. This is certainly true of a good number of Haydn’s symphonies: the earlier ones were initially played to a private audience, but the composer’s growing fame resulted in his being commissioned to write his final dozen for performance in London, in what turned out to be immensely popular public concerts. Some of Beethoven’s first symphonies also received double premieres – one in private and a later one open to all comers – before his standing ensured that, if his aristocratic patrons wanted to hear the first performance of the later ones (No. 5 onwards), they had to go along to a public concert with everyone else.

The programme for 'Mr Haydn's Night' at the Hanover Square Rooms on 16 May 1791, during the composer's first visit to London. Among the soloists, Nancy Storace is of particular note: she had lived in Vienna in the 1780s, where Mozart had written the role of Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro for her.

Concertos were a slightly different beast. Because they were designed to show off the skills of the soloist, the latter was placed front and centre of the programming: it was in this context that Beethoven initially made his mark on Viennese audiences, with performances of his own piano concertos. This ultimately led to the rise of the virtuoso musician, to all intents and purposes a 19th-century rock star whose skill and charisma sometimes resulted in overwhelmed audience members fainting. These performances could be driven by a spirit of virtuosity for its own sake: there is a reason why Paganini is better remembered as a violinist than a composer today, while Liszt has an equal footing in the pianist and composer camps. (Leaning into the rock star parallels, the latter was played by none other than Roger Daltry, lead vocalist of The Who, in Ken Russell’s 1975 film Lisztomania, with Ringo Starr as Pope Gregory XVI thrown in for good measure.)

Even as a more formal type of concert was gradually taking root alongside these excesses, the pot-pourri approach hadn’t entirely fallen by the wayside. Like music-hall or (in more recent times) the sketch show, it allowed for considerable variety within the space of a single evening: if one item left you cold, it wouldn’t be long before something would take its place. As such, it could draw considerable crowds, and it would have been easy to programme nothing but what we might now call wall-to-wall bangers. A series called Mr Robert Newman’s Promenade Concerts took a different tack, its chief conductor Henry Wood deliberately pushing the envelope with performances of new or unfamiliar works alongside the classics. This philosophy will be familiar to anyone who attends these events (now the BBC Proms), though for a time there were some clear trends: Friday emerged as Beethoven Night, while Monday was devoted to Wagner – shorn of voices in what is sometimes still termed ‘bleeding chunks’, less daunting to the casual music fan than a full opera.

Purism appears to have prevailed, however, with these varied programmes having largely fallen out of favour. There have been attempts to reintroduce a more 18th-century spirit to concerts since, but these have largely been notable for their curiosity value. These have exposed modern audiences to the radical notion of breaking into applause in the middle of a movement if they enjoyed a particular passage, something so commonplace in Mozart’s day that he deliberately worked two such moments into the first movement of his Symphony No. 31, Paris.

The concert-going experience may have changed too much for us to feel absolutely comfortable with such levity, but equally, the overture-concerto-symphony format no longer really holds sway either. If it’s not been usurped by any viable alternative, this has resulted in enormously varied programming, minimising any risk of stagnation. There will always be some performances designed along tried-and-tested lines, but the unpredictability of others ensures the continued interest of audiences and players alike.

Related Stories

![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!![]()

The medieval carol

24 November 2025

For this year's Christmas article, we look back at some very early festive carols ...