Not quite a symphony: the sinfonietta, divertimento and serenade

13 Oct 2025

News Story

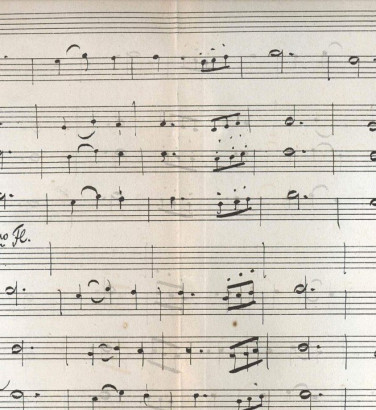

Detail from the cover of the SCO Wind Soloists' recording of Mozart

This article is part of a series for the 2025/26 Season in which we consider different aspects of the symphony - or in this case, slightly smaller-scale works which don't quite make the cut.

If the symphony is now regarded as the genre to which composers turn if they wish to make a Statement, this is largely thanks to Beethoven. Haydn (and, to some extent, Mozart) had left it as a work around which a concert programme could be built, but Beethoven’s, imbued with their creator’s force of personality, demanded attention like never before.

Most subsequent composers with an important number of symphonies to their name typically took a little while to build up to this standard: Schubert’s true voice arguably didn’t emerge until his No. 8, Unfinished, and while Mahler’s No. 1 bears many of the hallmarks of his style, it is easily eclipsed by his No. 2, Resurrection. Brahms got around the issue by biding his time before composing his own No. 1, while many other shied away from the genre altogether, preferring to turn their attentions to something less imposing.

The titles of some of these works conjure up images of a scaled-down symphony. This is certainly true of the sinfonietta, where the addition of a diminutive to the Italian word sinfonia suggests something more light-hearted. It would be wrong to suppose, however, that these works are any easier to perform: Poulenc’s Sinfonietta, for instance – a work the Orchestra performed in early October this year – may veer towards the flippant, but requires a lot of concentration from its players!

We should also mention any symphony whose title implies something smaller-scale, such as Gounod’s Petite Symphonie (actually written for wind nonet) and Britten’s Simple Symphony for strings, based on music he had written as a child. The addition of an appropriate adjective can do a lot to temper audience expectations, and these works are all the more charming for their unpretentious nature.

Schumann's Overture, Scherzo and Finale – which opens our Schumann & Mozart matinee concerts (13-15 November) – stands slightly apart from these. The composer himself had wished to designate this his Symphony No 2, only for his publisher to refuse on the grounds that it lacked a slow movement. The work has never quite recovered from being lumbered with a frankly ungainly title, but behind this lies music as engaging as any of Schumann's symphonies proper.

Less ambitious composers also had the option of using a different name altogether to show that their music didn't have such high aspirations. There’s a certain of amount of crossover between the likes of the divertimento and serenade, both consisting of anything from four to ten movements, generally alternating fast and slow, a pattern sometimes broken up by the inclusion of a minuet or other dance.

How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank!

Here will we sit and let the sounds of music

Creep in our ears: soft stillness and the night

Become the touches of sweet harmony.

Let us start by looking at their roots in the Classical era. The serenade’s origins as a nocturnal piece sung at someone’s window spilled over into its recasting as an instrumental work, often also intended for outdoor performance. (Britten would later play on this by selecting poetry on the subject of night for his Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings.) This may account for the number of serenades written specifically for wind instruments, whose sounds carry more easily in the open air than strings, but there are exceptions – not least one of Mozart’s most beloved works, the serenade for string orchestra better known as Eine kleine Nachtmusik.

Besides sonic considerations, cellos and double basses being less portable than their wind counterparts meant that string ensembles were better suited for indoor entertainment. In this context, the divertimento was expected to provide unobtrusive accompaniment at social functions, a disregard which may explain why it all but died out in the 19th century (as composition became a more serious business). It would, however, go on to enjoy a minor revival in the 20th century, for instance in Stravinsky’s Divertimento from his ballet Le baiser de la fée or Bartók’s Divertimento for Strings.

The serenade had, by this point, more or less ousted the divertimento, moving firmly indoors during the Romantic era, when those written for strings – by Dvóřak, Tchaikovsky, Elgar and Wolf (Italian Serenade) – fast became mainstays of their repertoire. There would also be examples for larger orchestras, including by Smyth and Sibelius, though the best-known are probably Brahms’ pair.

Composed to all intents and purposes as part of his self-imposed preparation for writing a symphony, Brahms nonetheless stuck to the loose structure of the Classical model. Both include at least one minuet and scherzo, and end with a crowd-pleasing rondo. Beyond this, an interesting feature is their instrumentation: the first was originally scored for a mixed wind-and-strings nonet, and there are no violins in the second.

Today, these lighter alternatives may not rank as highly in general estimation as the symphony, but they certainly have their place in concerts. As in so many other respects, variety is the spice of life, and it does no harm to have an equally mixed musical diet: could we really consider the serenade and leave out Glenn Miller?

Related Stories

![]()

Making a splash: water music beyond Handel

5 January 2026

We take a look at musical depictions of water, from trickling burns to the wide expanse of the ocean, to see what lurks below the surface.![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?