Opera seria: a beginner's guide

9 Jun 2025

News Story

Kathleen Ferrier as Orpheus, 1949

The two operas performed by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra in this year’s Edinburgh International Festival – Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice and Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito – may have been written almost three decades apart, but their composers are key figures in the history of the artform. In this pair of masterpieces, both reacted to what had come before, seeking to correct the course of opera in a direction which made better sense to them.

The genre had grown considerably since its creation by Jacopo Peri in the last years of the 16th century, and by the 1710s had split into two distinct categories. Orpheus and Tito are both examples of opera seria, retellings of tales from mythology or (generally ancient) history, leaving more comic subjects the preserve of opera buffa. (For a time, one-act opera buffa would even be performed in the interval of the more highbrow opera seria.) By the 1740s, however, opera seria was increasingly hampered by starry casts demanding music to showcase their talents, and even opera buffa had started to stagnate.

It was at this point that Handel threw in the towel with opera and shifted his focus to composing oratorios, coincidentally at the same time as Gluck’s first stage works were produced. With experience, the latter was among a number who came to object to opera being dominated by virtuoso singing for its own sake, which he felt sidelined the genre’s dramatic content. Gluck wished to see nothing less than a complete reversal of this situation, putting the drama centre stage, with every other element – even the music – being recast so they are in service to it.

Thus it was that, in 1762, Gluck pared back all the excesses of Baroque opera in Orpheus and Eurydice: with its streamlined plot and only three named characters, this is music so beautiful in its simplicity that any virtuosic display would be entirely out of place. It’s as though the composer were showing his audience that no bells and whistles should be needed to amplify Orpheus’ devastation at the untimely death of his wife Eurydice. He is prepared to venture into the Underworld to bring back her soul and that, frankly, should be enough. The subject-matter may still be straight out of Greek legend, but the characters’ humanity has been restored, and the sense of restraint only adds to the opera’s emotive content.

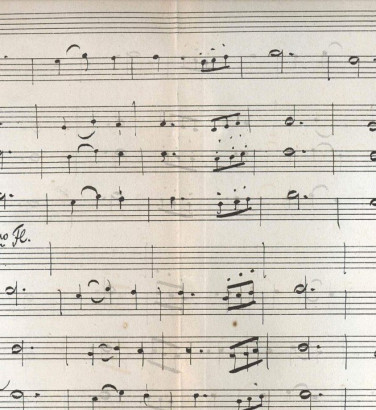

The role of the librettist in opera is often overlooked, and here we should highlight Gluck’s collaborator Ranieri de’ Calzabigi: the two were of one mind, going on to write another two operas together. The preface to the second of these, Alceste, even sets out their stall with a declaration of intent: after an overture with a clear connection to the plot of the opera (whether in its general mood or specific themes), the words of the libretto should be set in such a way that they can be easily understood. This meant simplifying the vocal lines (leaving no opportunity for unnecessary embellishments), allowing the plot to progress not by means of dry recitative but in the musical numbers, along with a reduction of repeated text in the latter – all steps towards making the drama more engaging.

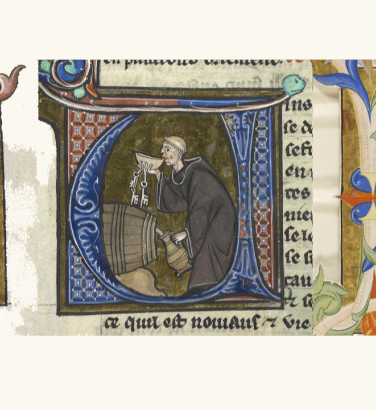

Pietro Metastasio

The pre-eminent librettist of opera seria before these reforms was the Italian poet Pietro Metastasio, whose libretti (nearly 30 in number) were the basis for over 800 operas. Not that his poetry was immediately abandoned after Orpheus and Eurydice was premiered: Gluck's final Metastasio setting would come three years later, and Mozart's own operas show a gradual transition to a new approach. He left the text of Il sogno di Scipione unchanged when he set it in 1772, but turned to one Giambattista Varesco to edit his Il re pastore three years later.

The libretto Varesco wrote for Mozart’s Idomeneo (another Greek legend) in late 1780 was entirely his own, and by this time the latter had enough confidence and experience writing opera to insist on having a good deal of say in the text. The working relationship between the two became increasingly fractious and later fell apart altogether. Mozart himself would give opera seria a wide berth until 1791 (his final year), when he was commissioned to write La clemenza di Tito – for which he dusted off a libretto by Metastasio (coincidentally set by Gluck nearly four decades previously), which was reworked by the poet Caterino Mazzolà to reflect changing tastes. This included condensing the original’s three acts into two and creating ensemble numbers to replace a good deal of recitative, though crucially, the moral of the story (about the importance of a ruler showing compassion) remained intact.

The popularity of opera seria was very much on the wane by this point, however, possibly reflecting the aristocracy’s fall from grace as revolutionary movements spread across Europe. The 19th century saw mythological and historical tales from the ancient world dropped almost entirely from the operatic stage. (Berlioz’s epic Les Troyens is something of an exception, though its sheer scale can be said to have worked against it: it was not staged complete until the 1920s, half a century after the death of the composer.)

In their place would come streams of literary adaptations: Shakespeare came into his own, along with more recent authors from Walter Scott (Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor) to Alexandre Dumas (Verdi’s La traviata), with Pushkin understandably resonating very strongly with Russian composers. Those interested in myths and legends, in the meantime, tended to turn to their native cultures, giving us operas such as Dvořák’s Rusalka, Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel and Wagner’s Tannhäuser. (Der Ring der Nibelungen is a more questionable inclusion here, being based on a medieval German retelling of Norse legends.)

Back in the 18th century, opera seria sometimes had a tendency to moralise, so any more recent opera with a clear lesson to impart could be said to continue in its vein, whether it’s Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov examining the weight of personal guilt, or the ostracisation of the individual in Britten’s Peter Grimes. We can add to this the operatic treatment of Biblical subjects once deemed unsuitable for representation on stage, from Verdi’s Nabucco to Saint-Saëns’ Samson and Delilah. For all that the term opera seria may be rather outdated today, the genre still survives in spirit.

Mozart's La clemenza di Tito

Step into ancient Rome with Mozart's La clemenza di Tito - the SCO's performance at the Edinburgh International Festival.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Journey to the underworld and back with Opera Australia and the SCO, presenting Opera Queensland's production of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Related Stories

![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!![]()

The medieval carol

24 November 2025

For this year's Christmas article, we look back at some very early festive carols ...