Musical hoaxes

27 Oct 2025

News Story

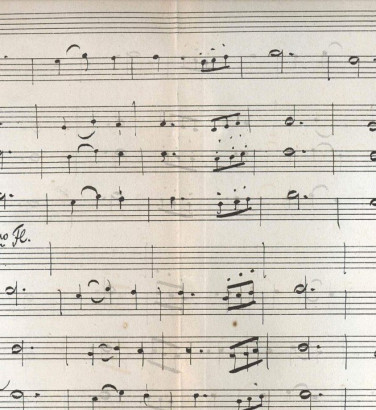

Three composers involved in (or on the receiving end of) subterfuge: from left to right, Berlioz, Mozart and Kreisler

Berlioz’s oratorio L’Enfance du Christ (performed by the SCO on 27-28 November) owes its existence to a modest piece the composer wrote for his friend Joseph-Louis Duc in 1850. Originally for organ, he added voices to this music before giving it a second airing, this time under the name of the (fictitious) 17th-century composer Paul Ducré, whose original manuscript he had apparently struggled to decipher. The performance was a resounding success, presumably leaving egg on the face of the audience member who claimed its charm and simplicity were beyond Berlioz when the latter revealed he was its true composer.

This is the story behind the best-known movement of L’Enfance du Christ, the chorus known in English as 'The Shepherds' Farewell'. As hoaxes go, it’s one which worked very much in Berlioz’s favour, but have other composers also sought to mislead their audiences, and to what end?

Perhaps the best-known of musical leg-pulls, one sustained over several decades, was the violinist Fritz Kreisler’s claim that a good deal of the music he performed in his recitals was written (or at least based on works) by composers of yesteryear. A small core of his nearest and dearest knew perfectly well Kreisler had written all these pieces himself, but as far as the wider public knew, they were the work of (perfectly genuine) Baroque composers. It may have helped that many of these were no more household names then than they are now – Francœur, Martini or Pugnani, anyone? – but he threw in a few more familiar names for good measure, such as Boccherini or WF Bach.

To say he muddied the waters somewhat would be an overstatement. He acknowledged some pieces (such as Syncopation) as his own, the Rondino on a Theme of Beethoven likewise (accurately acknowledging its origins), initially claimed his Alt-Wiener Tanzweisen (Old Viennese Dances) as being by Lanner only to copyright them under his own name in 1910, a full quarter-century before he admitted he'd actually written the lot. This eventual revelation had probably been on the cards for some time: not unreasonably, people had started to wonder how Kreisler had exclusive access to a treasure-trove of unknown old works. The fact they were all written for his own instrument could be seen as a bit too much of a coincidence.

A less successful deception had been attempted over a century earlier by one Count Franz von Walsegg, an Austrian with an interesting approach to becoming known as a great composer: he commissioned others to write music which he then passed off as his own work. His ambitions came slightly unstuck in the early 1790s. Seeking to mark the first anniversary of his wife's death, he made arrangements to pay Mozart for the composition of a Requiem mass, only for the composer himself to die before he could complete it. Left in financial straits, his widow Konstanze indulged in some subterfuge of her own, eventually getting her husband's pupil Franz Süssmayr to finish the work, with the intention of palming it off as genuine Mozart.

Rather impressively, her stratagem worked: von Walsegg had ‘his’ Requiem performed in late 1793, unaware that the piece had already been premiered earlier that year, under Mozart's name. Peter Shaffer's play Amadeus adds an additional twist to this tale, with Salieri hearing rumours about Mozart being visited by a mysterious cloaked figure with this commission and precipitating his rival's final illness by donning the same disguise to put pressure on him, only to be astonished when the stories turn out to have been perfectly true. (The 1984 film has the older Salieri tell the story of his relationship with Mozart after being committed to a psychiatric hospital, effectively excusing any historical inaccuracies by dint of his being an unreliable narrator.)

A decade earlier, Mozart himself had successfully duped his former employer, Archbishop Colloredo, who had commissioned six duos for violin and viola from Michael Haydn (younger brother of Joseph). The two composers had been colleagues in Mozart's Salzburg days, and when Haydn fell ill after completing only four, his friend happily stepped in to help. Colloredo was apparently none the wiser, and given his difficult relationship with Mozart, it's easy to imagine the latter being very satisfied with the success of the deception.

Despite Süssmayr's completion of the Mozart Requiem (which you can hear in our concerts on 30 April and 1 May) coming in for some criticism since, it has at least stood the test of time, which is more than can be said for the piece dubiously known as Albinoni’s Adagio. Once heard in all sorts of film and media – it showed up in Flashdance and Blackadder in the 1980s alone – it has gradually fallen from favour, possibly owing to the advent of historically-informed performance. According to its creator, one Remo Giazotto, it is based on “two thematic ideas and a figured bass by Tomaso Albinoni” which he found in the Saxon State Library in Dresden at the end of World War Two, despite the city being all but destroyed by bombing raids in February and March 1945. The manuscript has never come to light, and with our current understanding of Baroque music, the decidedly over-egged piece Giazotto created from some fragments (which may yet have been perfectly authentic) seems more of his own time than Albinoni’s.

It is, however, all too easy to criticise: there can be an undeniable sense of fun to musical hoaxes, even a degree of admiration. Winfried Michel, who successfully fooled Haydn experts with a set of piano sonatas in 1993, elicited the admiration of BBC Music Magazine for the quality of the imitation. It is, after all, the sincerest form of flattery.

Related Stories

![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!