Haydn, Father of the Symphony

22 Sep 2025

News Story

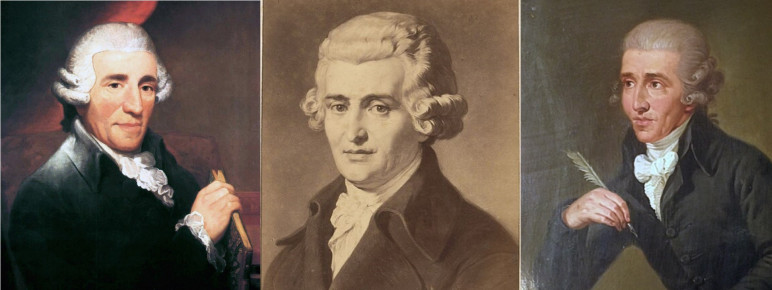

Three portraits of Joseph Haydn

This article is part of a series for the 2025/26 Season in which we consider different aspects of the symphony - which would not be complete without a look at the composer known as its father.

Haydn’s role in developing the symphony in its early days has long been recognised. The dozen he wrote for performance over two visits to London in the 1790s – including No. 103 (Drum Roll), which the SCO played in October – can be regarded as the genre’s first high water mark, proof not just of its musical qualities but also that it could form the focal point of a concert programme. Beethoven would further cement its significance in the early 19th century, but what had Haydn actually done to be recognised (to this day) as the father of the symphony?

Let us start by dismissing any argument that puts it down to the number he wrote. True, he is among the few composers whose symphonies reach treble figures (106 in his case), but then so did Graupner, Molter, Graun, Pokorný and Dittersdorf, all of them similarly active in the early days of the genre. The consistently high quality of Haydn’s output is what truly marks them out: our own Principal Guest Conductor Andrew Manze wondered, in an interview for this website last year, if there was such a thing as a bad one. The untold advantage this gives Haydn's symphonies – it's thoroughly enjoyable using them to track the development of the genre through them – is countered by a number of them being unjustly overlooked despite their many qualities. No. 56 in C (which opens our Haydn & Schubert concerts, 15-17 January) would probably be more widely recognised as the fine symphony it is ... if it weren't competing for space with 105 others.

The story of the symphony begins long before Haydn, however, in 16th-century Italy. It was here that the term sinfonia was first used to denote a piece of music, typically a sacred vocal work, though at this stage the word meant nothing more than ‘sounding together’. It would shed the voices to become a purely instrumental piece over the course of the 17th and early 18th centuries, often set within a larger work – not that its precise position was set in stone. Handel’s Messiah, for instance, opens with a Sinfony for orchestra (what would later be called an overture), and the sequence in which the birth of Christ is announced to the shepherds is introduced by another instrumental movement, known as the Pastoral Sinfony (not to be confused with Beethoven’s or Vaughan Williams' symphonies of the same name).

These two pieces are single movements, in contrast to the three-movement structure favoured by this point back in Italy: fast, slow, then fast again (and often dance-like). As if to emphasise that the genre had yet to take final form, these works could be called either sinfonia or overture, the latter reflecting their occasional use as curtain-raisers for operas. There was a similar lack of consistency in Germany, where the terms overture and suite were used interchangeably to describe their own orchestral work of choice, a revamped version of the suite beloved of slightly earlier French composers. This was made up of a sequence of dances, which they prefixed with a third kind of overture, this one consisting of a slow, stately introduction that gives way to a faster section, the latter fuelled by a single idea that is passed around the entire orchestra in imitation. The symphony would eventually emerge from a combination of all these, effectively a pan-European musical fusion.

I listened more than I studied and therefore, little by little my knowledge and ability were developed.

To the south of the Alps, an overlooked figure now enters the story: the Italian composer Giovanni Battista Sammartini, who played a key part in raising the sinfonia from its rather perfunctory status as an introduction to a greater piece into something more substantial, capable of standing on its own two feet. This was in large part due to his approaching the genre with the same respect granted to the likes of the concerto, works in which there was more opportunity for developing musical themes. Audiences' constant hunger for new music resulted in Sammartini being largely forgotten after his death – it was not until Mendelssohn rediscovered Bach in 1829 that music of the past started to be appreciated – but his innovations had clearly set the ball rolling.

Surprisingly, Haydn is not known to have made any mention of this. Towards the end of his life, putting a decidedly positive spin on the isolation he had experienced during most of his working life, he said that there had been “no-one to confuse or irritate me, and I was compelled to become original.” He had written some symphonies before taking up a post with the Esterházy family in 1761 – the exact number is difficult to pin down - but his creative streak went into overdrive at this point. One of the earliest he composed for his new employers may well be the first with an additional movement, in the form of a minuet tucked between the slow movement and finale. This courtly dance, which had migrated from the German suite, gradually ensconced itself as an integral part of the Classical symphony. It would admittedly be superseded by the more nimble (and sometimes acerbic) scherzo by Beethoven, but the four-movement symphony has remained a standard ever since.

Even without broadening our listening to symphonies written by other composers, it quickly becomes clear how fast the orchestra was expanding at the time. The Baroque foundation of strings had already been amplified by pairs of oboes and horns, along with a single bassoon. A second would eventually join the fold, a pattern repeated with the flute before two clarinets completed the woodwind family. Trumpets and timpani were used as and when a more festive atmosphere was required, before they too became a permanent fixture. (This would go on to form the basis of the modern chamber orchestra, including the SCO.)

As orchestra leader I could try things out, observe what creates an impression, what weakens it, in other words improve, add, cut out, take risks.

Not that this progression was entirely linear: Haydn benefitted from having larger orchestras at his disposal than most, so it's more useful here to look at Mozart, whose last three symphonies (also performed by the SCO this Season, 29-31 January) may well have been the result of a purely creative urge. As such, their instrumentation can be taken as an indication of a more idiosyncratic approach, each being tailored to suit the mood of the music. Nos. 39 and 41 forgo oboes and clarinets respectively, and the latter are present only in the revised (more frequently performed) version of No. 40, whose more sombre mood is reflected in the absence of trumpets and timpani. Beyond this, bassoons, horns and strings are found consistently in all three symphonies, along with a single flute.

Where Haydn's symphonies really come to life is the way they show him constantly experimenting, trying out new ideas. Thus the central (trio) section of the Minuet in No. 11 has one part always lagging behind the others by half a beat, the oboes are replaced by cors anglais in No. 22 (Philosopher), the slow movement of No. 62 teases at a melody that never quite materialises, he asks the strings to turn their bows upside-down at one point in No. 67, No. 88 plays with a hurdy-gurdy-like drone in its trio … The list goes on and on, but at no point does Haydn let the grass grow under his feet.

Even in his final symphonies, there’s still a sense of his inviting us all, musicians and audiences alike, to find out what else could be done with the genre. He may have called it a day in 1795 (a pragmatic decision for a 73-year-old), but he had clearly left his mark on the symphony, guiding it into what might be termed early adulthood before passing on the torch. Beethoven would be the first to take it to new heights, but (pace Sammartini) it was Haydn who first recognised its true potential.

Related Stories

![]()

Making a splash: water music beyond Handel

5 January 2026

We take a look at musical depictions of water, from trickling burns to the wide expanse of the ocean, to see what lurks below the surface.![]()

Mozart and the symphony

22 December 2025

Stuck between the symphonies of Haydn and Beethoven, where do Mozart's fit in?![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?