Vaughan Williams and the revival of English music

13 Nov 2023

News Story

From left to right: George Butterworth, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Gustav Holst

Victorian England, as far as the European mainland was concerned, was a place to be pitied. “The land without music” was one German critic’s pithy summation in 1904, though the idea had already been floating around for almost 40 years. Alarmingly, some parts of the English music scene appeared to agree, or at least be thoroughly unimpressed with what music there was: the so-called pastoral style which came to prominence in the early 20th century was seen as a bit lightweight, mocked by Elizabeth Luytens (herself an English composer) as the Cowpat School in the 1950s.

Sad to relate, there is some justification behind the first of these unflattering descriptions: to this day, many would be hard-pushed to name a prominent English composer between Purcell and Elgar, born two centuries apart. Luytens' epithet, however, as entertaining as it is, does not take into account that stylistically, English music was notorious for lagging behind the times, so it is hardly surprising that it should also rediscover its native folk music long after the rest of the continent had moved on to pastures new.

The school she disliked so much had emerged at the tail end of the 19th century, at a time when many promising newcomers were launching their careers. Of these, Gustav Holst would come to feel The Planets overshadowed his far more important work as a teacher, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor became one of the most prominent composers of African descent of the age, and too many others – including George Butterworth, known to countless singers for his settings of AE Housman’s A Shropshire Lad – lost their lives in the First World War.

All three of these composers are linked to a single man through friendship, shared periods of study at the Royal College of Music and a common interest in collecting English folk songs respectively. This was Ralph Vaughan Williams, probably the pre-eminent representative of the pastoral school.

The art of music above all the other arts is the expression of the soul of a nation.

Vaughan Williams is notable for the breadth of his interest in older English music, especially that of the Tudor period. Greensleeves, the basis for his Fantasia of the same name (actually drawn from his opera Sir John in Love, an adaptation of The Merry Wives of Windsor), may also have found its way into Holst’s St Paul Suite, but Vaughan Williams’ love of Thomas Tallis – the inspiration for another beloved Fantasia, with which Maxim’s Baroque Inspirations in December 2023 culminated – was peculiar to him. This relatively early work was among the composer's first successes, with The Times recognising a timeless quality in the music at its 1910 premiere: “it cannot be assigned to a time or a school," its reviewer wrote, "but it is full of the visions which have haunted the seers of all times.”

Broadly speaking, the influence of England’s musical heritage on the country’s composers has dwindled since. Benjamin Britten made no secret of his debt to Purcell, but as far as English folk music is concerned, it’s now largely a thing of nostalgia fuelled by the likes of The Archers’ theme tune – which may sound like Vaughan Williams but is actually by his near contemporary Arthur Wood. Malcolm Arnold's dance suites (including two sets of English Dances) pay a more lighthearted tribute to the folk music of the British Isles, and more recently, the Christmas perennial Walking in the Air (from Howard Blake's score to The Snowman) has a timeless quality to it which is unmistakably folk-inspired.

Beyond this, however, there is little doubting that English music has long since caught up with the times. Vaughan Williams himself played a key role in this, being more multifaceted a composer than his pastoral works - including the evergreen The lark ascending - would suggest. His Fourth and Sixth symphonies are unexpected strident, and he is among the earliest composers of note to have written for the silver screen, 1948's Scott of the Antarctic being probably the best known of his film scores. He may have been in his mid-70s by this point, but Vaughan Williams remained a true modernist, setting an example for generations to follow.

Related Stories

![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!![]()

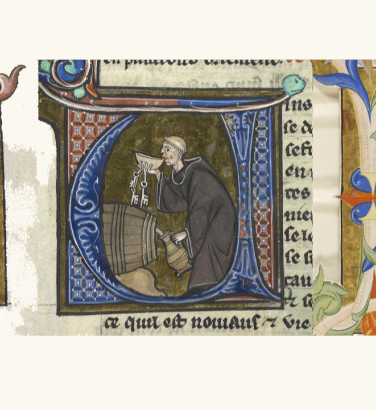

The medieval carol

24 November 2025

For this year's Christmas article, we look back at some very early festive carols ...