The re-emergence of Czech music

23 Oct 2023

News Story

Left to right: Bedřich Smetana, Leoš Janáček, Antonín Dvořák.

Even in its late 18th century heyday, the Austrian empire may not have extended across the vast areas of others, but still covered such a swathe of eastern Europe that many cultures had been absorbed by it. Just as political rebellion reared its head across the continent over the course of the 19th century, so composers rediscovered and embraced their country’s musical heritage.

If Vienna was no longer quite the musical epicentre it had been, a wider Germanic school remained predominant across Europe, and debate raged as to how artists could best reflect their native culture. A thoroughly idiomatic style was all very well for shorter compositions such as Chopin’s Mazurkas or Grieg’s Lyric Pieces, but applying this to larger scale works opened a whole can of worms. The symphony, which had become the most highly regarded form of musical expression, followed a number of conventions, placing it immediately at odds with the more freewheeling nature of folk music. Reconciling these two extremes was therefore something of a tightrope walk for composers. In fact, most of the 19th century would elapse before this was done to general satisfaction, hence Tchaikovsky’s early symphonies remaining much less known than his later ones.

Despite the fact that I have moved considerably in great music circles, I still remain what I have always been – a simple Czech musician.

Although music had always been an important part of life in Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic), few of its pre-19th century native composers are known to us today. There has admittedly been a revival of interest in Biber and Zelenka in recent years, but even their reputations hardly rest on any Bohemian flavour in their music, despite the efforts of Adam Michna to introduce a folky inflection to his secular works in the 17th century. It was not until 1870 that a recognisably Czech work would gain international prominence: this was Smetana’s opera The Bartered Bride, whose composer played such a vital role in establishing his country’s musical style that he is regarded as the father of Czech music.

The likes of Dvořák and Janáček were not far behind, being two and three decades Smetana’s junior respectively, and if the music played by the SCO Wind Soloists in their Side by Side concerts in autumn 2023 is not among their best-known, it is worth noting that the skill of Bohemian wind players had been long recognised. The on-stage wind octet in the finale of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, written in 1787 for the Prague National Theatre, is a fine tribute to Bohemia’s musical heritage, one which the country’s own composers would continue to develop over the years.

Related Stories

![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Andrew Manze: "I've always loved Viennese waltzes and polkas"

1 December 2025

Our Principal Guest Conductor is really looking forward to conducting our Viennese New Year concerts!![]()

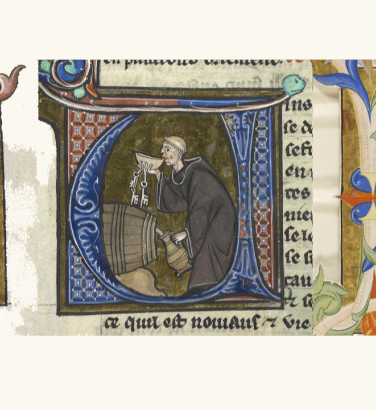

The medieval carol

24 November 2025

For this year's Christmas article, we look back at some very early festive carols ...