Mozart's last piano concerto: why is it underrated?

24 Nov 2022

News Story

The piano concertos Mozart wrote from late 1784 to early 1786 - numbered from the late teens into the early mid-20s - are held up as a peerless series of masterpieces, one made all the more extraordinary by the short period over which they were composed.

Perfectly valid as opinions go, but it does have the unfortunate effect of leaving the rest unduly overlooked. While the earlier ones can be legitimately viewed as leading up to this creative peak, it is all too easy to dismiss the few that came afterwards as a brief tailing-off. Unfortunately, there may be grounds for this in the case of his Piano Concerto No 26, Coronation: the constant dialogue between piano and woodwind that is always a highlight of the mature Mozart is noticeably absent, so the work can feel like a step backwards stylistically.

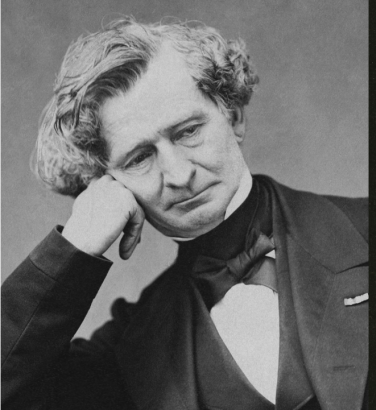

The Mozart family, c. 1780: Mozart and his sister Nannerl are seated at the piano, their father Leopold is holding a violin; a portrait of their mother Anna Maria (who had died in 1778) is on the wall.

This inevitably - and rather unfairly - has a knock-on effect on No 27, when it’s actually very much a return to form. The fact that Mozart would write no more piano concertos afterwards robs it of context, as we can't know how it would have fitted into the wider scheme of things. As a result, it stands out as something of an anomaly before even considering the music itself.

Outwardly perfectly cheerful, this last piano concerto contains several hints of the autumnal atmosphere that was creeping into Mozart’s late works, including the much better-known clarinet concerto. The brilliance typical of the earlier concertos seems a touch muted, as though a light fog were lingering on the horizon.

This is one of the concertos of very few in the whole piano repertoire that really is transcendent. I think the ones that have that power are this one, Beethoven’s Fourth, Brahms’s First and Bach’s D minor Keyboard Concerto – works that just take you to a higher place.

This final piano concerto therefore occupies a middle ground in the set: while nowhere near as dark as the two written in minor keys, the effortlessly chipper mood which had pervaded the earlier concertos is noticeably absent. Instead, the score is scattered with glimpses of minor keys, giving the music a fascinating sense of ambiguity. It suggests a new sense of maturity in the composer: once the young buck, he is now a considered adult – giving us all the more reason to regret what might have been, had he not died a year of its first performance.

Related Stories

![]()

Unfinished symphonies

15 December 2025

Your starter for ten: besides Schubert, who has an unfinished symphony to their name?![]()

Musical hoaxes

27 October 2025

Dishonesty among classical composers? Surely not!![]()

Figaro beyond Mozart (and Rossini)

20 October 2025

Where does Jonathan Dove's 'Figures in the Garden' fit in with the Figaro story?