A history of the viola concerto, from Telemann to Miller

17 Apr 2023

News Story

Opening of Hoffmeister's Viola Concerto in D (c. 1780-1800)

Historically regarded as the poor relation of the string section, the viola has struggled to find a foothold as a solo instrument. Supposedly lacking the brilliance of the violin and the depth of the cello, it was commonly viewed as an instrument for violinists of limited skill, and initially did little more than doubling the cello part. Small wonder that it became the butt of musicians’ jokes.

A great deal of headway has been made in showcasing the potential of the viola as a viable instrument for solo concertos over the last century or so, but history weighs heavily on its reputation. The comparative lack of pre-20th century viola concertos has left a sizeable gap in its repertoire, so those which do survive are to be treasured all the more.

The question of survival is worth stating: the first known viola concerto is by Telemann, believed to have been written between 1716 and 1721. There may of course be an earlier example awaiting discovery somewhere, but given this composer’s fascination with instrumental colours, it is entirely plausible that he should have been the first to explore the viola’s potential as a solo instrument.

Not that Telemann’s concerto made much impact on the wider musical world: half a century later, a concert was erroneously described by one writer as featuring “the first viola concerto ever heard”. This 1772 performance was the debut of one Alessandro Rolla as both composer and soloist: a name all but forgotten today, despite his being the author of well over a dozen viola concertos. He is better remembered as a key teacher of Niccolò Paganini, of whom more later.

The 1770s would be an important decade for the viola concerto, with the brothers Carl and Anton Stamitz writing seven between them, but they would be eclipsed (at least in our eyes) by Mozart’s discovery of the instrument, as encapsulated in his 1779 Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola. True, the viola does share the limelight with the violin, but it is very much an equal partnership, and Mozart instructs the soloist to tune their instrument a semitone sharper than usual, brightening its sound to help it stand out.

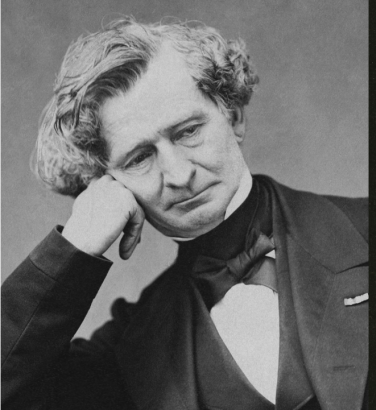

This would turn out to be another flash in the pan, however, with the next important work for solo viola and orchestra not coming about until 1834. Even then, Berlioz referred to Harold in Italy as a symphony with solo viola, so it’s debatable whether it’s even a concerto. Written at Paganini’s request, the latter took against the work when it was still in sketch form, unhappy with what he regarded as the soloist having insufficient music to play.

A contrite Paganini apologises to Berlioz on hearing Harold in Italy, 1838

Several reasons have been put forward to explain why the viola finally gained recognition as a solo instrument in the 20th century. Among these are the purely musical, such as the popularity of the British violist Lionel Tertis, who would commission a great deal of new music for the instrument, including Walton’s concerto and Vaughan Williams’ Flos campi (as performed by the SCO with Timothy Ridout in May 2022). His legacy would be taken up by William Primrose, for whom Bartók wrote his viola concerto. As violists themselves, Hindemith and Britten also made important contributions to the instrument’s repertoire.

From a psychological perspective, there is also a theory that the sound of the viola came to mirror the mood of the time. Concertos for the violin and cello can often rest on their ability to convey brightness and passionate emotions respectively. The viola can be seen as treading a middle ground between these, all underscored by a sense of melancholy – a reflection of an increasingly fractured world.

The same can of course be said of the uncertainties of our own century, and the viola has thus come into its own. As Covid 19 took hold in 2020, the violist Lawrence Power was behind a series of Lockdown Commissions as a response to the pandemic. Among the composers featured was Cassandra Miller, the UK premiere of whose Viola Concerto he gave with the SCO (one of the work’s co-commissioners) in May 2023.

The work has been reviewed by the New Yorker critic Alex Ross as ‘immensely beautiful and immensely haunting’. He could have been writing about the instrument itself.

Related Stories

![]()

Musical hoaxes

27 October 2025

Dishonesty among classical composers? Surely not!![]()

The percussion concerto

1 September 2025

Our examination of the concerto now turns to percussion. Expect the unexpected!![]()

The clarinet concerto

16 June 2025

It's the clarinet's turn to step centre-stage for a look at their concerto repertoire. It's possible Mozart is mentioned!