Brahms's Chamber Passions: the art of musical conversation

26 Jan 2023

News Story

We think nothing of attending recitals of chamber music today, but the genre was originally intended for private performance, typically by amateur aristocrats. It was perfectly normal for a group of musicians to come together to play music for their own pleasure; if there was any audience, it consisted of people close to them.

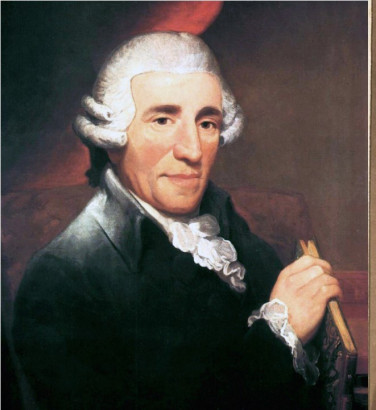

As such, the music they performed tended to reflect this sense of intimacy: it would be written as a form of idealised discourse, the type in which everyone had something to contribute but no-one truly dominated the conversation. Joseph Haydn’s string quartets are very much along these lines, and just as he established the conventions of the symphony, so his take on this pre-eminent genre of chamber music continues to hold sway to this day.

There were exceptions even then, of course, but this was usually for a specific reason. If the cello is unusually prominent in Mozart’s so-called Prussian quartets, for instance, this was a deliberate ploy to flatter their commissioner Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, who played the instrument. The same is true of the copious amount of music Haydn wrote for the baryton, a (now long obsolete) stringed instrument beloved of his employer Prince Nikolaus Esterházy.

One hears four rational people conversing together, and imagines gaining something from their discourse.

Otherwise, it was generally only when another part was added to the standard string quartet that one of them – more often than not the additional instrument, especially if it came from a different part of the orchestra – would be allowed to stand out, but even then, maintaining equilibrium remained a prerequisite. Upsetting this delicate balance could easily result in one of the players losing interest.

Things had already started to shift by the early 19th century, however. Beethoven’s 1796 quintet for piano and wind instruments put the keyboard to the fore – quite unlike its inspiration, Mozart’s much more democratic quintet for the same instruments – and works such as his Violin Sonata No 9 (the Kreutzer) were conceived on so grand a scale that they positively demanded public performance. That said, Schubert’s circle of intimate friends continued to enjoy music-making in private, hence the abundance of piano duets (possibly the most domestic of any musical genre) among his works.

Brahms also wrote a wealth of chamber music steeped in this Viennese tradition. Although he composed his Piano Quintet (with which our Brahms’s Chamber Passions concert on 26 February culminates) within only two years of his moving to the Austrian capital in the early 1860s, it amply exemplifies the ideal of a musical conversation between equals: it may have been written at a time when chamber music had moved out of the aristocratic drawing room to the concert hall, but the audience still has the sense of being invited to listen in on erudite discussion among friends. Small wonder that it is widely acknowledged as one of the very finest of any work of chamber music.

Brahms's Chamber Passions

Led by Aylen Pritchin and Maxim Emelyanychev, join an ensemble of SCO players on an exploration of Brahms's chamber music in all its variety.

Related Stories

![]()

Haydn, Father of the Symphony

22 September 2025

In the latest in our series looking at the symphony, what makes Haydn so significant in its development?![]()

Symphonies and their nicknames

8 September 2025

Beethoven's Fifth has a nickname? Well, it does according to some people ...![]()

Beethoven's 'lesser' symphonies

26 May 2025

Why are some Beethoven symphonies better-known than others?